Main menu

You are here

Home ›Opinion: ‘Yes, No and Careful’ to Dennis Tito’s Bold Mars Expedition

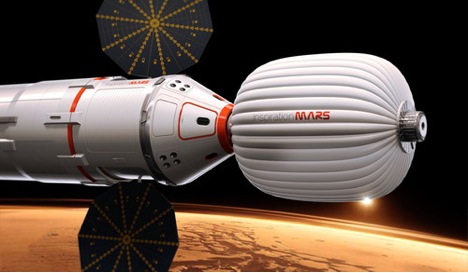

Now that the initial public reaction to Dennis Tito’s press release about his Inspiration Mars plan has died down, it’s time to take a good look at the nuts and bolts of this idea. In case you missed it, Tito and a group of aerospace manufactures and NASA scientists are proposing to send two people on a 1.4 year Mars flyby in 2018, using a combination of off-the-shelf hardware but with some needed development.

The detailed work, presented in a paper to IEEE Aerospace conference in March, shows that these people are serious, and have spotted an unusual (these 1.4-year solutions only appear every 15 years) opportunity for a remarkable adventure. It’s early days, of course, but I have mixed feelings about the mission as it stands. On the one hand, the thing is massively inspirational and would catapult the humans-to-Mars program ahead by a decade or more. You’ve got to love that. The development of the needed technologies would also be hugely advantageous to space travel in general. Demonstration of the will of private capital to exceed what government agencies can now do would also be a big help to exploration. You might even get in some science done during the voyage.

On the other hand, in the event of an accident, public opinion could turn against such space adventures very sharply. The public is not good at comprehending risk and payoff these days. The proposed voyage is very risky, and depends on a some untried technology. The Dragon would probably be mature as a spacecraft by 2018, but it would not have taken people out of Earth orbit, even as far as the moon. To stake the whole project on one great voyage is not good risk management. I believe that one of the reasons project Apollo succeeded was that it was willing to patiently solve the many problems it faced one step at a time by running missions of increasing complexity. Yes, I know there won’t be an Apollo-scale budget this time, but neither are there so many problems to be overcome. Tito’s mission is technically a lot simpler now than a moon landing was in the 1960s. Therefore, I would suggest two test flights, one into LEO and the second around the moon, to ensure a reliable spacecraft, communications, navigation and life support and the rest.

Those ECLSS (Environmental Control and Life Support Systems) are complex machines which would have to be ready pretty soon to be able to test them sufficiently to stake lives on their reliability. It would not be too soon to start gathering the components for that and building duration-testing rigs. My main concern, though, would be the physical health of the two astronauts. I’m not convinced that we’ve yet completely licked the bone mineral-loss and other effects of prolonged microgravity. You’ll be aware that this has been an obstacle to long-duration crewed missions in microgravity. We’d want to see some pretty convincing drug-and-exercise results before betting human safety on it. Of course, that task must be worked on, and may well be conquered given time, but I think the authors would agree that not having a good solution to that should be a showstopper. I also worry about the radiation dose they’d suffer in the event of a Solar Particle Event or violent event producing ionising radiation. There’s not much provision for shelter on a ship that size.

I studied psychology for many years before getting into robot engineering. Psychologically, the trip is tough, but not especially dangerous for a well-chosen pair. Contrary to amused public opinion, well-trained and properly balanced couples are not especially likely to come into dramatic conflict in that kind of time frame, even in such cramped conditions. On a final note, I see that the current plan does not include a provision for spacesuits. Bad idea, and one which would surely come back to haunt the mission planners in the event of trouble. You don’t know what you might need to do to keep the ship functioning for that long, and not being able to depressurise the spacecraft for short periods of time, or leave the spacecraft not only deprives the mission of important photo opportunities, but greatly reduces options available to the crew in the event of unexpected incidents.

Yes, let’s do it, by all means. But remember the lessons of history about success in difficult tasks in space. Run a simpler, less risky mission first to build up confidence and experience (e.g. lunar orbit). Get started early on the really big questions, including in this case the reliability of life support systems (begin reliability testing of at least the components immediately) and methods of protecting the crew during the long voyage (best methods available against muscle loss, bone calcium depletion and radiation dosage). Build flexibility into your systems to proof them against unknown problems (include spacesuits).

Then we’ll be ready to do it properly.

Dr Graham Mann, Mars Society Australia

The full paper can be found at: